ALBA Synchrotron

Crocodile bones and teeth, from the existing Nile specie and also from fossils dated 70 million years ago, have been analysed at the ALBA Synchrotron. These life records offer information about crocodiles’ biology and evolution, from the Cretaceous to the present. The study is carried out thanks to the collaboration among the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM), the University of Alcalá (UAH), the CSIC Institute of Ceramics and Glass (ICV-CSIC) and the University of Vic - Universitat Central de Catalunya (UVic-UCC). This innovative interdisciplinary scientific team gives a new approach to research, including the perspective of materials science to biology and palaeontology.

Crocodylus niloticus, Bernard Dupond.

Samples of crocodile bones and teeth belonging to both Nile species (Crocodylus niloticus) and their relative ancestors, who lived at the end of the Upper Cretaceous about 70 million years ago, have been studied at ALBA. The research from the UAM, UAH, ICV-CSIC and UVic-UCC has included experiments at the MSPD beamline using X-ray powder diffraction technique.

The main goal is to find the similarities and differences between these bones and teeth, which unveil information not only about animals growth and physiology but also about how the crocodylomorph groups lived under different past ecosystems. As ectotherm animals, their growth is affected by environmental conditions. "Crocodiles, like all animals, use strategies to adapt to the environment, which can be unstable. They suffer environmental changes now and they suffered them in the past too. They can be affected by colder weather or by an oil spillage for example; and all these situations are carved out in the animals. The key is to discover how this information is recorded (in their tissues, at a chemical level...) and how to understand it", explains Óscar Cambra, professor and researcher at the UAM. Similar to tree rings, "the growth of both teeth and bones is a reflection of crocodile lives and a good record of the environmental changes they have lived", he concludes.

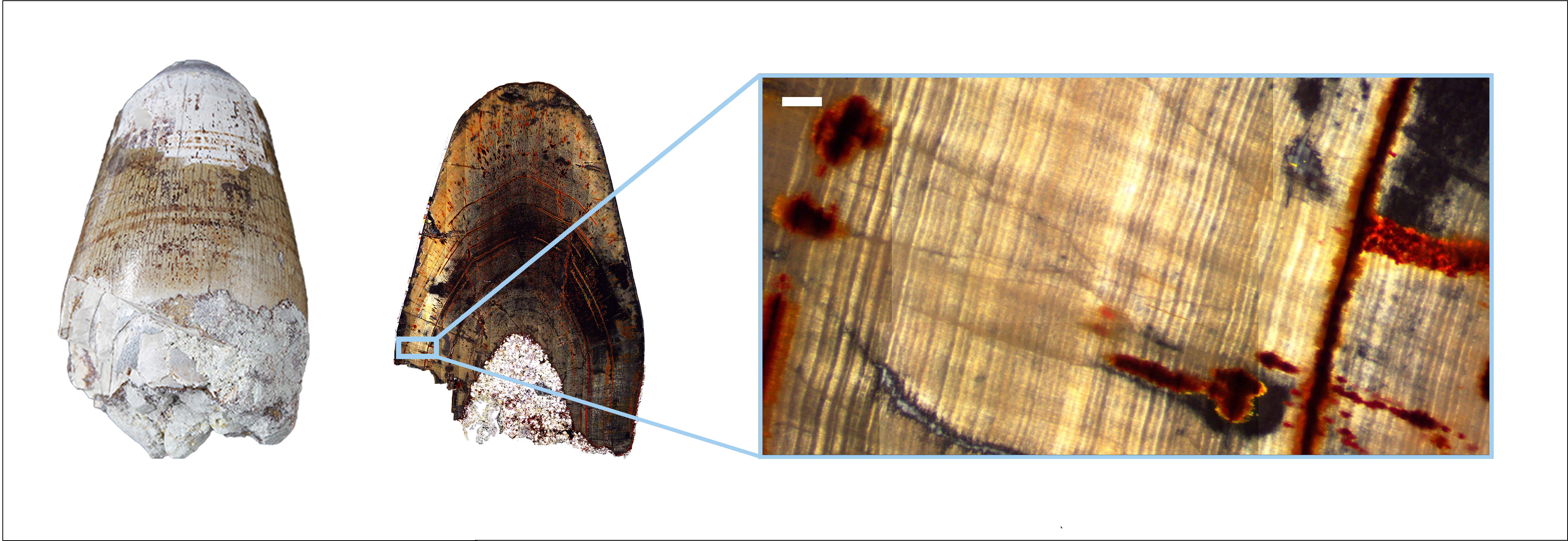

Scientists want to compare these teeth and bones samples that belong to existing and extinct crocodile species and thus, study if the current environmental changes have the same impact for current crocodiles than those in the past. Using electron microscopy, some differences between fossil and extant individuals samples have already been observed; now researchers want to discover the reasons behind them.

From left to right: Oriol Vallcorba, ALBA beamline scientist; Julia Audije, PhD student at UAM; Miquel Colomer; María Canillas, postdoctoral researcher at ICV-CSIC; Óscar Cambra, professor and researcher at UAM; and Judit Molera, researcher at UVic-UCC.

One of the novelties of this study is the strong collaboration between two research fields: materials science and biology. The is widely used to study materials such as minerals, ceramics or glass, but it is also useful for studying organic material. "In fact, bones or teeth are just a material that could be studied and characterized as ceramics", explains María Canillas, postdoctoral researcher at ICV-CSIC.

Such high resolution offered by synchrotron light diffraction enables to identify morphological changes in tissues not appreciated with other techniques. "Unlike other kinds of equipment that also use X-rays, ALBA provides us much more detailed analysis. We can select a specific area in the sample and see precisely what happens there: changes in composition, in textures, in crystalline orientation...", says Canillas. Changes in bones and teeth can be analysed from the materials science perspective and then, understand this information from a biological point of view.

"These differences in teeth and bones of existing and extinct crocodiles may be due to changes occurred at different levels: individual level, due to the evolution of the species or for some environmental reasons," explains Julia Audije, PhD student at UAM. "It can also be a mixture of these factors or even there could be another one that we are not considering," she adds. In addition, she points out that they have to be careful when generalising conclusions since "crocodiles, for example, change their dentition approximately every 80-260 days. Although you only have a register for a specific limited time of the whole animal life, we try to get the most information from the life record provided by the tooth, and also by the bone."

Researchers are convinced that with these analyses, carried out for the first time at the Synchrotron, they will be able to obtain much more information. It is also worth-mentioning the valuable collaboration established between the team of biologists and geologists from the UAM and the UAH, and the experts in materials science. According to Cambra, "perhaps we would have never come to ALBA without the help of Judit Molera's team from the UVic-UCC and Miguel Ángel Rodríguez Barbero's group of the ICV-CSIC, who are widely experts on synchrotron powder diffraction techniques." In their opinion, the use of the MSPD beamline "is a challenge for us and a new research opportunity that opens the door for a new approach to biology and palaeontology".

With the collaboration of Fundación Española para la Ciencia y la Tecnología. The ALBA Synchrotron is part of the of the of UCC network from the FECYT and has received support through the FCT-20-15798 project.