ALBA Synchrotron

In a recent publication, researchers from French and Spanish Institutions used the combination of two synchrotron light characterization techniques to study Chinese blue-and-white Ming porcelains, which are decorated under the glaze with Cobalt-based blue pigments, and produced during a one-step firing at high temperatures. They were able to identify the firing temperature by determining the porcelain’s pigments and the reduction-oxidation media conditions during their production. The approach they used can also be applied on a broad range of modern and archaeological ceramics to elucidate their production technology.

Pottery is found at the majority of archaeological sites dating from the Neolithic period, when first human settings appear, onwards. Which makes it a major focus of study in archaeological science. The study of style and production of ceramics is central to the historical reconstruction of a site, region and period.

More specifically, ceramic technological studies look to reconstruct the production technology of ceramics, by determining the selection and preparation of the raw materials, the formation of ceramics, treatment and decoration of the ware’s surface and the firing atmosphere. All of this is possible thanks to the scientific techniques available nowadays.

In a recent publication, researchers from French and Spanish Institutions used the combination of two synchrotron light characterization techniques to study Chinese blue-and-white Ming porcelains. These characteristic porcelains, whose production flourished around the 14th century, are decorated under the glaze with Cobalt-based blue pigments that provided their distinctive blue decorations and produced during a one-step firing at high temperatures.

They were able to identify the firing temperature by determining the porcelain’s pigments and the reduction-oxidation media conditions during their production. The approach they used can also be applied on a broad range of modern and archaeological ceramics to elucidate their production technology.

The origin of the Cobalt-based blue pigments used varied. For instance, an Iron-rich Cobalt ore was imported from Persia and mainly used from 1279 to1423 AD, and its utilization leaded to the formation of characteristic Iron-rich dark spots on the blue decorations. Later on, the spread use of a Manganese-rich Chinese cobalt ore resulted in formation of Manganese-rich dark spots.

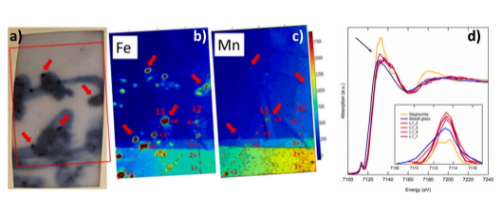

In this work, the studied samples correspond to a sherd from a large bowl presenting numerous and visible dark spots, dated from the Chenghua (1464-1487 A.D.) and Hongzhi (1468-1505 A.D.) reign of the Ming Dynasty from the Jiangxi area. Researchers performed X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) experiments at the CLÆSS beamline in the ALBA Synchrotron, to probe the chemical variations in the ceramic decorations associated to the development of the porcelain’s dark spots.

The authors team results from a scientific collaboration involving young researchers among national and international institutions and large-scale facilities between France and Spain: the CEMES of University of Toulouse, the University of Barcelona, the Natural Science Museum of Barcelona and ALBA synchrotron. The first author of the study is Professor Josep Roqué-Rossell, from the Faculty of Earth Sciences and the Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology from the University of Barcelona (IN2UB).

Porcelain Jar with cobalt blue under a transparent glaze (Jingdezhen ware). Mid-15th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Synchrotron light: looking without destructing

XRF and XAS are non-destructive mapping techniques that allow the spatial determination of atomic elements and how their chemical species distribute in the sample. Researchers specifically characterized the distribution of manganese and iron ions in the porcelain's matrix.

The obtained results suggested that during the porcelain’s firing the manganese and iron ions diffused, moving from regions of higher concentration to regions of lower concentration. During cooling, the ions crystallized as the oxide minerals rhodonite and hausmannite-jacobsite, which are intermediate compounds. This helped identifying the temperatures achieved during their production. In addition, the detailed study of the Iron XAS provided to be a powerful tool to assess the reduction-oxidation record in the porcelain’s glaze.

Finally, they were able to determine the oxidizing conditions achieved during the blue-and-white Ming porcelain production by comparing the obtained results to those of natural basalt, as a calibration method.

The Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty ruled in China from 1368 to 1644. It is considered one of the greatest eras of social stability and disciplined government in human history. Under its rule, an extensive fleet and army were built and numerous construction projects were carried out. Some as well known as the Grand Canal, the Great Wall, and the founding of the Forbidden City in Beijing.

Although the production of blue and white porcelain dates back to the 7th century AD, it was under the Ming dynasty that they were produced and exported at large-scale to South-West Asia, Eastern Africa, Middle-East, and Europe.